Reflections: Water for the Environment in Victoria, 2022-23

31 October 2023

Reflections highlights actions in 2022-23 by the Victorian Environmental Water Holder (VEWH) and our partners to support the health of waterways, landscapes and communities through the Victorian environmental watering program.

Click here to download a PDF version of Reflections 2022-23

![]() [PDF File - 24.1 MB]

[PDF File - 24.1 MB]

Partners who work with us to put the program into action include waterway managers in nine catchment management authorities (CMA) and Melbourne Water, other environmental water holders, storage managers, land managers, Traditional Owners, and scientists. Our stakeholders are those organisations and people with an interest in the environmental watering program.

Water for the environment in Victoria

Water held for the environment in storages helps to support our rivers and wetlands since natural flows were changed through the introduction of dams, weirs, channels and other infrastructure in many river systems to support important human needs.

Water for the environment looks to provide outcomes such as:

- cueing fish migration and breeding

- improving water quality

- improving the condition of floodplain trees

- triggering the growth of wetland plants, and

- providing feeding and nesting habitats for waterbirds.

Management of water for the environment aims to build resilience and halt declines in species as the climate changes. Each year watering actions are managed in response to seasonal conditions, including responding to natural events, such as the 2022 floods.

Waterway managers plan with Traditional Owners, stakeholders and communities to enhance shared benefits when environmental flows are delivered including for Traditional Owner cultural values, recreation and social values and community wellbeing.

Our reflections on 2022-23

The flooding events that spanned almost the entire state of Victoria in late 2022 were felt well into 2023 and still leave people impacted today in some parts of the state. But even when it’s wet, water for the environment can be used to meet environmental objectives.

Across much of 2022 – 23 program managers moved to adapt to unexpected effects of large scale flooding across Victoria. The culmination of three back-to-back La Niña events and several years of wetter-than-average conditions peaked with record-breaking floods in some regions later in 2022.

The record-breaking rainfall during spring 2022 caused the biggest flood in recent history in the northern region of Victoria, with all major water storages filling and spilling. In large parts of the Gippsland region, wet conditions continued for the third consecutive year, even though floods there were not as big as two years ago.

In central Victoria many areas of greater Melbourne experienced their highest October rainfall, either on record or in the last 20 years, although summer and autumn were drier than the long-term average. For the western region, there were exceptionally wet months between September and December, followed by drier than average conditions in autumn.

Environmental water managers stood back through spring, stopping watering actions that had started, while prevailing wet conditions replaced planned watering and produced results the program continues to assess.

Emergency efforts

Small volumes of water were delivered to parts of rivers in northern Victoria experiencing hypoxic blackwater, in the hope that fish could find refuge in distinct areas of better-quality water while the blackwater event passed through.

Waterway managers’ actions like emergency efforts to salvage native fish, pre-emptive deliveries of environmental water from irrigation outfalls to create fish refuges, and close monitoring of dissolved oxygen levels may have helped prevent more fish deaths.

After the floods water managers were assessing the outcomes, learning from what was happening on the ground, and focusing on the best combination of environmental watering actions to be delivered for changed conditions.

Blackwater had a major impact on current fish populations and there was a proliferation of carp following the floods. Waterway managers and environmental water holders had to determine where environmental flows were needed to support waterbird breeding and fish spawning and migration, and where to hold off flows to minimise the risk of further increasing carp populations.

Helping waterbirds breed and feed

Normal summer and autumn environmental flows were delivered in many rivers after the floods had peaked. Fairly dry conditions had returned, dams had stopped spilling and harvesting from major rivers was back to normal. Most wetlands were still holding water so there was generally no planned floodplain watering through autumn.

When waterbirds breed after natural floods it’s vital to give them every chance of success for their hatchlings to reach maturity. Extra water was delivered in February and March to some wetlands where floods had triggered breeding later than usual, so that birds had water for food, nesting sites, and protection from predators for their chicks to fledge and become independent.

Waterbird breeding responds well to large natural floods, but there must also be enough food in subsequent years to enable them to survive to breeding age. Maintaining adequate foraging habitat near key waterbird nesting areas will be a priority for environmental water managers in 2023-24.

The next important stage after flooding is deliberately letting wetlands dry out for the next year. Shallow margins of drying wetlands provide abundant foraging habitat for wading waterbirds and the muddy bases of drying wetlands are rapidly colonised by lakebed herbland plant communities. A range of broad-leaved herbs, grasses, sedges, rushes and shrubs have adapted to survive under both wet and dry conditions and flourish as wetlands draw down.

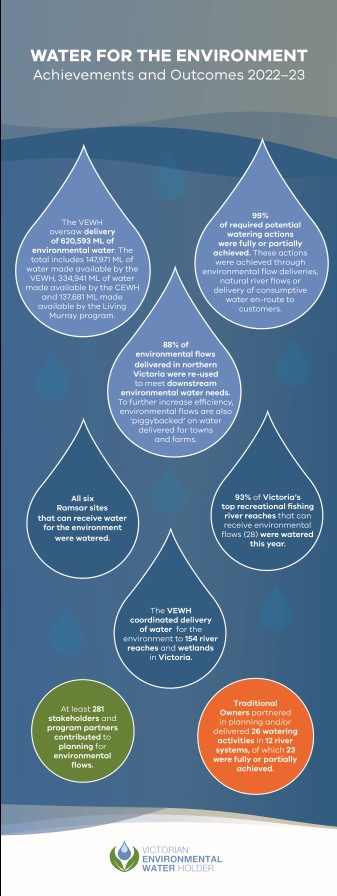

A snapshot of program achievements and outcomes for 2022-23

620,593 megalitres (ML) of water for the environment was delivered by partners in the environmental watering program across Victoria, in line with priorities published in the Seasonal Watering Plan 2022-23.

This includes water managed by these water holders and programs:

- Victorian Environmental Water Holder – 147,971 megalitres

- Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWH) – 334,941 megalitres

- The Living Murray (TLM) program – 137,681 megalitres

These deliveries and the associated volumes for each waterway system are reported in our Summary of Water for the Environment Delivery

Achievements and outcomes in 2022-23

These snapshots highlight the program achievements and outcomes of water deliveries for 2022-23. They resulted from planning and active coordination between partners, deep engagement with Traditional Owners and communities, and the combined efforts of waterway and land managers to take care of water, land and biodiversity from the top to the bottom of Victoria’s catchments.

Water on Country

The VEWH is committed to increasing the self-determination and agency of Traditional Owners in the environmental watering program. The Victorian Government policy document Water is Life: Traditional Owner Access to Water Roadmap was released in 2022, providing a framework for Traditional Owner water access and management, including for environmental water.

In 2022-23 the VEWH continued to work with Traditional Owners both directly and through waterway managers, to strengthen the Traditional Owner self-determination and agency in water delivered for environmental outcomes.

The case study on Lake Boort outlines in DJAARA’s (Dja Dja Wurrung Aboriginal Clans Corporation) words how environmental flows can heal Country and the benefits that can be gained when Traditional Owners are empowered to fulfil their custodial obligations.

Read Djarra's Lake Boort case study by clicking here.

Gippsland region

West Gippsland had its third very wet year in a row in 2022, testing communities again after major flooding across the region in 2021.

Natural flows from spilling reservoirs and local catchment run-off met most planned watering actions during the year.

Rain and storage releases and spills flushed the Latrobe, Macalister and Thomson rivers across winter and spring. Water for the environment was not needed in the Macalister or Latrobe rivers at all because the natural flow met or exceeded flow recommendations.

Upper sections of the Latrobe River catchment received their highest total June rainfall in 24 years. Thomson Dam spilled in October for the first time since 1996.

Sustained high river flows and low salinity have produced signs of better ecological condition in West Gippsland rivers and wetlands, including:

- breeding in the Latrobe estuary of estuary perch and Australian bass at a scale not seen in recent decades

- freshwater plants like ribbon weed growing in large areas across the Heart Morass wetland at levels not seen for many years

- the vulnerable green and golden bell frog successfully reproducing in Heart Morass

- large-scale breeding of royal spoonbills, little black cormorants pied cormorants and Australasian darter in Dowd Morass, the biggest breeding event seen since the floods of 2010-11

- continued high numbers of tupong and river blackfish in the Thomson River, including in the reaches upstream of Horseshoe Bend where river restoration works completed in 2019 enabled permanent fish passage to 80 kilometres of the Thomson and Aberfeldy rivers.

A second consecutive year of high allocations of water for the environment in the Snowy River was able to be delivered to mimic seasonal snow melt patterns to boost the river’s ecological and physical conditions.

Read our Gippsland case study by clicking here.

Central region

Wet conditions generated by a La Niña weather pattern continued in central Victoria for the third year in a row.

Intense rainfall in spring generated high river flows, flooding, and spills from some storages in the Tarago, Yarra, Werribee, Moorabool and Barwon systems.

The high rainfall and subsequent flooding across greater Melbourne during October 2022 was unprecedented, with many areas experiencing their highest total October rainfall on record, and others the highest total October rainfall for at least 20 years.

Spills and high natural river flows took care of and exceeded many watering actions that had been planned for the year to allow fish movement and breeding, waterbird and frog breeding, boost growth in plants and food for native fish and other animals, flush waterways and improve water quality.

Large natural floods achieve this to a much greater extent than environmental flows, but they can also harm some species and the landscape. For example, the floods may have drowned young platypus in low level burrows, caused bank erosion and boosted growth in pest plants on floodplains.

All the lower Yarra (Birrarung) River billabongs were inundated, some for the first time in 10 years. Flood levels in the Barwon River rose over the banks to fill the wetlands Reedy Lake and Hospital Swamps, which form part of the internationally recognised Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula Ramsar site used by thousands of migratory birds from around the world.

As flooding and storage spills subsided, water for the environment was delivered in the Yarra, Tarago and Werribee systems under the seasonal watering plan’s wet scenario.

Read our Central case study by clicking here.

Western region

High rainfall in 2022 ended five consecutive dry years in western Victoria.

The Wimmera River and all tributaries had high flows that continued naturally through to late December. The catchment had its highest unregulated flows since 2011, with some areas being the wettest in 160 years.

Flooding started gradually in August, then spring rain quickly increased storage levels and boosted flows in the Wimmera River’s arterial system, with water pushing through the heart of the region and filling the previously dry Lake Hindmarsh to 65 per cent capacity. Many landholders were affected and broadacre crops were lost.

Wimmera CMA worked with Grampians Wimmera Mallee Water to direct excess flows into areas that do not regularly receive water, with Dock Lake near Horsham reaching an estimated capacity of 95 per cent.

Conditions began to dry out in December and water for the environment was used to deliver base flows and freshes in Burnt Creek, MacKenzie River and the Wimmera River from January. These watering actions were in line with the Seasonal Watering Plan 2022-23 and aimed to ease water quality issues, including low dissolved oxygen levels caused by the floods.

High flows in the Glenelg River peaked at nearly 16,000 ML per day through November and early December. Floods, natural high flows and passing flows met or exceeded the planned priority watering actions through spring and summer, which meant that water for the environment was only needed from March onwards.

The low use of water for the environment early in the year allowed a larger proportion of desired watering actions to be delivered through autumn 2023 without compromising potential watering actions in 2023-24 or beyond.

Surveys during March and April by the Victorian Environmental Flows Monitoring and Assessment Program (VEFMAP) reported large numbers of tupong moving upstream, indicating successful spawning and migration on the back of the floods and subsequent environmental flows.

The floods resulted in 100 per cent allocations for all entitlements in the Wimmera- Glenelg headworks system for the first time in many years. The boost in supplies of water available for the environment means a greater proportion of recommended flows can be delivered to the Wimmera and Glenelg systems in 2023-24.

Read our Western case study by clicking here.

Northern region

Flood levels in the Goulburn Broken catchment in October 2022 included the highest-recorded levels at Shepparton and Seymour and a one in 50-year major flood level at Caseys Weir and Orvale.

A peak flow of around 172,000 ML per day in the Murray River downstream of Yarrawonga inundated 100 per cent of the Barmah Forest floodplain.

Water quality deteriorated after the big floods and there were hypoxic conditions throughout the Murray system, including Gunbower Creek from late October to December 2022.

North Central CMA carried out emergency fish salvage to remove stressed fish from Gunbower Creek, moving more than 700 large-bodied native fish to parts of the upper Loddon River, Campaspe River and Kow Swamp that had higher dissolved oxygen, and to Victorian Fisheries Authority’s breeding sites at Arcadia and Snobs Creek.

In early February, some of the fish stored at Arcadia were returned to Gunbower Creek with Barapa Barapa Traditional Custodians. The rest were kept as brood stock to support future stocking programs.

The floods caused an increase in European carp across many systems that challenged water deliveries. Waterway and water storage managers and environmental water holders worked closely together to support native fish populations, support waterbirds and floodplain plant growth, and prevent further boosting carp populations.

Some watering actions were stopped to avoid redistributing carp. For example, fishways were closed in protected areas such as Gunbower Creek to prevent more carp moving up from the Murray. The autumn high flow planned in the Lower Goulburn River to help migration of juvenile native fish was cancelled after fish ecologists advised there were fewer than expected juvenile native fish in the Murray River and the flow would likely favour carp more than native species. Other environmental objectives from the Goulburn autumn flow were also not needed including supporting native bank vegetation which was in great condition following the flood.

While environmental flows aren’t able to provide the volumes needed to mitigate really low oxygen levels in places like the Murray River, small releases can make a difference at a local scale. An example is the Lower Broken Creek where environmental flows were used to oxygenate the water to help minimise fish deaths from blackwater.

Adaptive management will continue in 2023-24 in response to the previous season and the carp proliferation, with plans to draw down some wetland sites such as Reedy Swamp in the Goulburn system and Hird Swamp in Central Murray to reduce carp numbers.

Following the 2022 flood, Gunbower Forest had its largest waterbird breeding event for some years with more than 1,000 juvenile waterbirds recorded, while 835 young birds from threatened species like blue-billed ducks, musk ducks and magpie geese were recorded at the Central Murray and Boort wetlands. Environmental watering started again in June 2023 to support bird breeding and juveniles at this site with habitat and food sources, and continue the restoration of the river red gums.

Early monitoring has showed a halt in the decline of river red gums across Gunbower Forest and Guttrum and Benwell Forests, and positive understorey plant growth.

The floods elevated the priority of the combined autumn high flow in the Loddon River and Pyramid Creek to promote fish movement and help native fish recover.

Natural flooding at Wirra-Lo near the Loddon River created favourable conditions for the vulnerable growling grass frogs, and large numbers were recorded across the 11 wetlands within the Wirra-Lo complex that also support breeding of the endangered Australasian bittern.

Natural inflows from floods replaced planned water deliveries to most Central Murray and Boort wetlands. A notable exception was Kunat Kunat (Round Lake) where water for the environment was delivered in spring and autumn to maintain water and salinity levels within target ranges to support breeding and development of endangered Murray hardyhead fish.

Read our Northern case study by clicking here.

A final reflection

The VEWH's annual seasonal watering plan communicates where water held for the environment can be used across Victoria, based on emerging seasonal conditions and listening and adapting to what's happening on the ground.

The 2022-23 year was an excellent example of how being prepared for almost every eventuality helps to plan and deliver water for the environment for maximum benefit - before, during and after extreme conditions.

It’s not every year we get a big flood. In much of northern Victoria a flood of this size hasn’t been recorded since 1956, half a century before the VEWH was created over 10 years ago to manage environmental water. And it is certainly not every year that storages such as the Thomson Dam spill.

It is vital that we plan for different climate scenarios and have strong working relationships with program partner to collectively consider and make decisions as scenarios unfold.

Our environmental watering program adjusts to current conditions and seasonal variability, including our lived experience under accelerating climate change.

Watering actions in some systems aim to build on positive ecological outcomes achieved in recent years. In other systems environmental water will be used to support recovery from flood impacts like loss of native fish from hypoxic blackwater and loss of plants on the water’s edge of rivers, creeks and wetlands from bank erosion.

Supporting native fish will be a priority in coming years to help populations recover from the significant impacts of the extended hypoxic conditions in parts of some rivers.

“Thanks to our program partners, including Traditional Owners, and stakeholders for all their hard work, efforts and support,” said VEWH CEO, Dr Sarina Loo.

“Our program continues to work closely with people on the ground to learn how systems operate differently in the cycle of ‘boom and bust’ between record floods and drought, and everything else in between.

“The aim is to understand where in that cycle we can influence results in rivers and wetlands at a landscape-scale, and how can we track the influence of watering in dry years that translates to environmental benefits in wet years,” she said.

Further Information

For further information please call

03 9637 8951 or email

general.enquiries@vewh.vic.gov.au.